Chapter 3: Britain is European

22 October 2019. Up to a million people marched through central London, with over 150 coaches coming from all over the country. Formally they marched for a ‘final say’, a referendum on the Brexit deal, but in practice overwhelmingly out of support for the EU and the desire for Britain to remain a member. It was Britain’s biggest mass march since the anti-war demonstrations of 2003.

A million may not be much as a percentage of the population, but any time so many people are on the streets, in practice millions more are represented. (We could also note that, even at moments when Brexit appeared imperilled, pro-Brexit rallies never rose above a few thousand.)

Polling bears this out – surveys continue to show robust support for EU membership among the British public. When asked ‘In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU?’, 48% now say it was wrong to leave, versus 40% for right and 12% don’t know (YouGov, 23 June 2021).

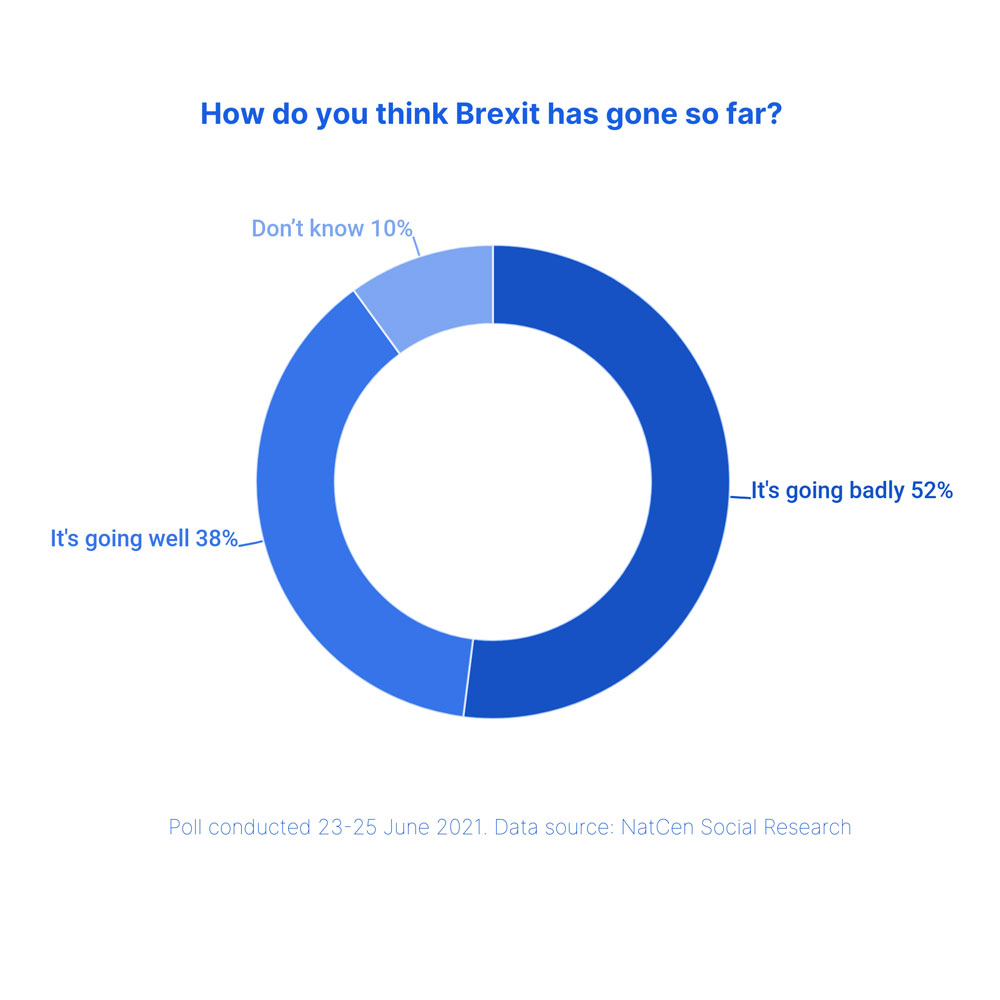

Remain vs Leave in a hypothetical new referendum is running at a slight lead for Remain, 47% to 46% (ComRes, 20 June 2021). Asking how well Brexit is going, meanwhile, gets a total of 52% for ‘quite’ or ‘very’ badly, compared to 38% for any of the ‘well’ choices.

Phrasing the question as being about ‘rejoining the EU’ does get a slightly lower result, depending on the poll, from 39% (YouGov, 23 June 2021) to 42% (ComRes, 20 June 2021). Both polls, however, currently have a large number of don’t knows. We should not be despondent about this: while rejoin is not quite currently a majority, it is still tens of millions of people! That is quite remarkable given the total lack of representation for rejoin in political parties and the press – there are few political positions that are so popular and yet so rarely put forward. The figure has a lot of room to grow as the effects of Brexit are felt, especially if a rejoin movement can get the arguments heard more widely.

The future is pro-European

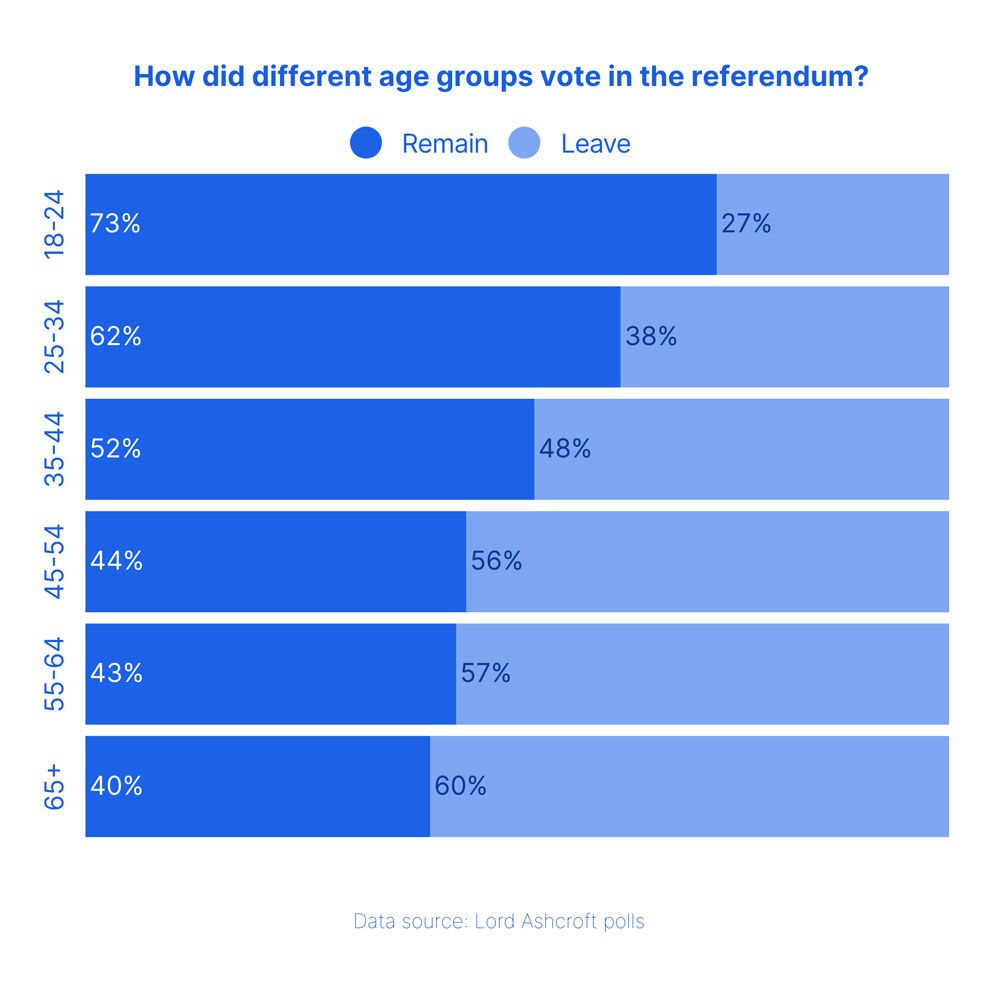

It is sometimes supposed, even now, that rejoining the EU is a question of ‘convincing Leavers to change their mind’. While it would be nice if they did, it is not necessary. Such high youth support for the EU means that over time, the shift in demographics as young people get the right to vote gives us the majority – in fact, it is very likely that this has already happened, and the effect will only get more pronounced as the years go by.

No one born this century voted for Brexit. With each passing year, this statement feels more and more dramatic. Students graduating from university in 2021 were too young to vote in the 2016 referendum. Out of the then-18-24 year olds who were able to vote, an estimated 73% backed Remain – in fact it was a majority in every age group under 45 (Lord Ashcroft Polls, 23 June 2016). Another poll in 2019 found that this trend continued after the Brexit vote too, with three-quarters of newly eligible voters who were too young to vote in 2016 saying they would back Remain in a new referendum (BMG, 10 March 2019).

While we have no desire to encourage age-based antagonism – a solid minority among older voters did still back Remain after all, and we know the pro-EU movement has many older stalwarts – there is a definite feeling among younger people that their future in the EU was voted away by people who already got to enjoy the opportunities in their lives (there are parallels to, for example, university tuition fees). For the large majority of young people, reversing Brexit is not a campaign to be approached gingerly, as if they need gently persuading – it is a matter of reversing an injustice committed against their generation.

We believe then that the primary task of rejoiners now is not to try to convince Leavers that they were wrong – much energy and funding has already been poured into this, to no avail. The question is not who is ‘persuadable’ but who is mobilisable. The more important task is sustaining a movement that builds support among the leaders of tomorrow, and looking for a moment when the question of EU membership can be put on the agenda once more.

The front foot next time

One thing the pro-EU movement does not generally want to reflect on, but is worth briefly mentioning, is that our current level of organisation was almost entirely built in the period after the referendum. While plenty of us did campaign in the referendum on the Remain side, it was only after the result came in that the anti-Brexit movement took to the streets, and a few years later that it cohered.

During the referendum, the leadership of official Remain campaign Britain Stronger in Europe (which was under the heavy influence of David Cameron and George Osborne) offered little but timidity and economics – the identity aspect was sidelined, the cultural arguments excluded, the threat to peace in Northern Ireland barely aired. In our view, those of us who were engaged in pro-EU campaigning at that point did not sufficiently insist on our independence from the incompetent official campaign, with many of us supposing that while we did not like the Cameron-Osborne ‘status quo’ messaging, they knew how to appeal to ‘middle England’ and win the referendum.

At the same time, it is fair to say that many who are now passionate EU supporters did not see the referendum as much of a risk until it was too late. It was not generally thought to be winnable for Brexit until the final weeks, and many of us were surprised at the strength of our own emotional response to the result. While the Brexiters had been preparing for their moment for decades, many Remainers didn’t know what we’d got until it was gone.

Our movement then spent three years growing stratospherically compared to before the referendum – but it was born into a rearguard battle, trying to win a new referendum at a time when there had just been one, with a Conservative Party that was being captured by the victorious Brexiters and a Labour Party doing its best to ignore the whole issue and hope it would go away. Once the 2019 general election foreclosed the immediate possibility of stopping Brexit, many of the new pro-EU organisations that had burst onto the scene disappeared just as suddenly.

But the connections and arguments we built during those years, when the possibility of stopping Brexit was at the centre of politics, are what we have to sustain us into the future. Some national pro-EU organisations continue, alongside many local ones. Stay European, for our part, was founded after the 2019 election, explicitly as an organisation for those who did not think it was time to wind down our movement. As the front page of our website states: ‘We are European – we will never give up.’

Having been born at one moment of defeat, and reborn at another, we must stay in this for the long haul now. If we can stay together, then having started on the back foot in 2016, we can start on the front foot next time.