Chapter 6: A change of government

This might be controversial, so let’s come out and say it: getting the Conservatives out of government is a precondition if we are to find a route to rejoin the EU. Two things follow from this quite closely. One, every bit of damage that we can do to the government and the Tory party aids the cause of rejoin. Two, we should campaign for the election of a non-Tory government, which in practice means either a Labour government or the coalition sometimes called a ‘progressive alliance’.

This seems obvious to us, and has lately become a mainstream position in the pro-EU movement. But at the edges of pro-EU campaigning still lurk some people who strongly dislike it: some (though very few!) are actual Conservatives, some overly value ‘cross-party’ status, tend to emphasise ‘good Tories’ and want to avoid an outright anti-Tory tone in order to make their campaigning safe for those very few pro-EU Tories who remain. (We understand that the European Movement national organisation, which involves many current and former Tory politicians, has broadly this position though refrains from saying so publicly.) This implies a focus on “holding the government to account” and implying that it is still possible to persuade the Tories to take a better direction on the question of the EU.

Let’s tackle this head on. Leaving aside any political positioning on left, right or centre, we can acknowledge that the Conservative party has historically included plenty of pro-EU politicians. Winston Churchill was part of establishing the project, Ted Heath was the prime minister who took Britain into the EEC, Margaret Thatcher backed ‘yes’ in the 1975 referendum on confirming our membership, and even David Cameron, who of course called the fateful 2016 referendum, campaigned for the ‘Remain’ side.

The developments in the party in the years after the referendum, however, are not just a temporary policy shift that can be pushed back the other way. The Conservative party has been transformed – remade in the image of Brexit, from its personnel to its electoral base. As former Tory MP Anna Soubry has said, the Tory Party is “now the Brexit Party, effectively”.

While this was not an overnight process, the watershed moment came when Boris Johnson withdrew the whip from 21 Tory MPs who refused to back his Brexit deal. They included Ken Clarke, who was the best-known pro-EU Tory, recent ex-chancellor Philip Hammond, Dominic Grieve, David Gauke, Justine Greening and Rory Stewart. Most infamously, Johnson even suspended Nicholas Soames, grandson of his supposed role model Churchill.

While some had the whip restored after an outcry, vocal support for Johnson’s Brexit deal was then made a precondition of being allowed to stand as a Conservative in the 2019 general election. Some of the rebels stood down from parliament, some ran as independents and a few joined the Liberal Democrats. Meanwhile, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party did a deal to stand down in favour of the Conservatives, and the Tories made “get Brexit done” their slogan for the election.

In the 2019 general election, MPs who had been turfed out of the Tories, or quit, over their pro-EU positions stood under a variety of other banners. David Gauke, Dominic Grieve and Anne Milton stood as independents against their former party. Former prime minister John Major backed the candidates who “were forced out of the Conservative party, and are now fighting this election as independent candidates”. Soubry, a pro-EU Tory until February 2019, stood for new party Change UK, and Sam Gyimah and Antoinette Sandbach were Lib Dem candidates, having joined the Lib Dems shortly before the election.

They did not see electoral success from this – but that is not the point. The Tory Party was systematically shorn of its pro-EU wing. Tory Remainers today have no representation in parliament and no prospect of challenging the leadership.

The Conservative government that faces us now is a Brexit government. The Tory party, Boris Johnson and Brexit have become the same project – inextricable from one another. The people who ran Vote Leave now sit around the cabinet table. The pro-EU movement has nothing to gain by being soft on the Brexit Conservatives whose takeover of the party is now complete.

To reverse Brexit, we must remove the Brexit government.

Progressive alliances

Ahead of the next election, support is growing for the idea of a ‘progressive alliance’. While there are various definitions from different campaign groups, it can be summarised as an alliance of the parties that have a chance to win seats and positioned on the centre-left or centre of politics – in practice, that means Labour, the Lib Dems, Greens, SNP and Plaid Cymru.

There is a ‘hard’ version of the progressive alliance idea where the parties would announce a formal pact, either standing down candidates in different seats or even standing under a joint electoral description. There is also a ‘soft’ version that puts more emphasis on local factors, standing down some candidates in some seats, or keeping a candidate in place but not campaigning very hard.

The full pact version would be a dream for many, but comes with some problems. The most immediate issue is that the party leaderships, particularly Labour and the Lib Dems, have no truck with the idea of an alliance. This isn’t just a matter of stubbornness as it is sometimes portrayed: the reason why it is possible for the Lib Dems to take seats from the Conservatives is that they are able to attract centre-right voters under some circumstances, but a formal pact would make it easy for the Tories to paint the Lib Dems as just an adjunct of Labour to these voters.

The question in any case is less what we would do in an ideal world, but what is possible in the circumstances we face. This is where local factors come into play. Where national party leaderships resist alliances, or where a formal pact would put off some section of voters, they can be constructed locally, whether it is explicitly or tacitly.

Two 2021 byelections offer a case study. The Lib Dems’ win in Chesham and Amersham saw them surge past the Tory candidate to win with 56% of the vote. Crucial in this was that Labour’s vote collapsed by 11 percentage points, down to just 1.6%. While this was reported in some publications as simply a disastrous result for Labour, the reality on the ground was that it represented deliberate tactical voting from Labour supporters. Tactical voting allowed for a win that would have been hard to hold together as a more formal alliance: around half of the Lib Dem majority appears to have come from Tory-to-Lib-Dem switchers, and the other half from Labour tactical voters.

The other byelection, Batley and Spen, was a narrow Labour hold against a strong Tory challenge. While the Lib Dems only had 4.7% of the vote in this seat in 2019, the byelection Labour majority was less than 1%, making the noticeable tactical voting from Lib Dem supporters once again crucial to the result.

Tactical voting has the advantage that it is not a prerequisite to persuade any party or candidate to stand down its candidate. Instead, persuasion efforts can be focused on the public at large – while they are generally harder to reach, they are also far less tribal in these decisions and more likely to respond to appeals to ‘keep out the Tory’. As the Tories move further to the Brexit hard right, the popularity of tactical voting has been rising accordingly, with an estimated 26% voting tactically in 2019 (Lord Ashcroft Polls, 13 December 2019). Many strides were made in 2017 and 2019 in setting up digital resources and social media campaigns to encourage tactical voting – not enough to overcome the particular circumstances of those elections, but a strong base for next time. If the leaderships won’t construct a progressive alliance, we can build one from the grassroots.

Proportional representation

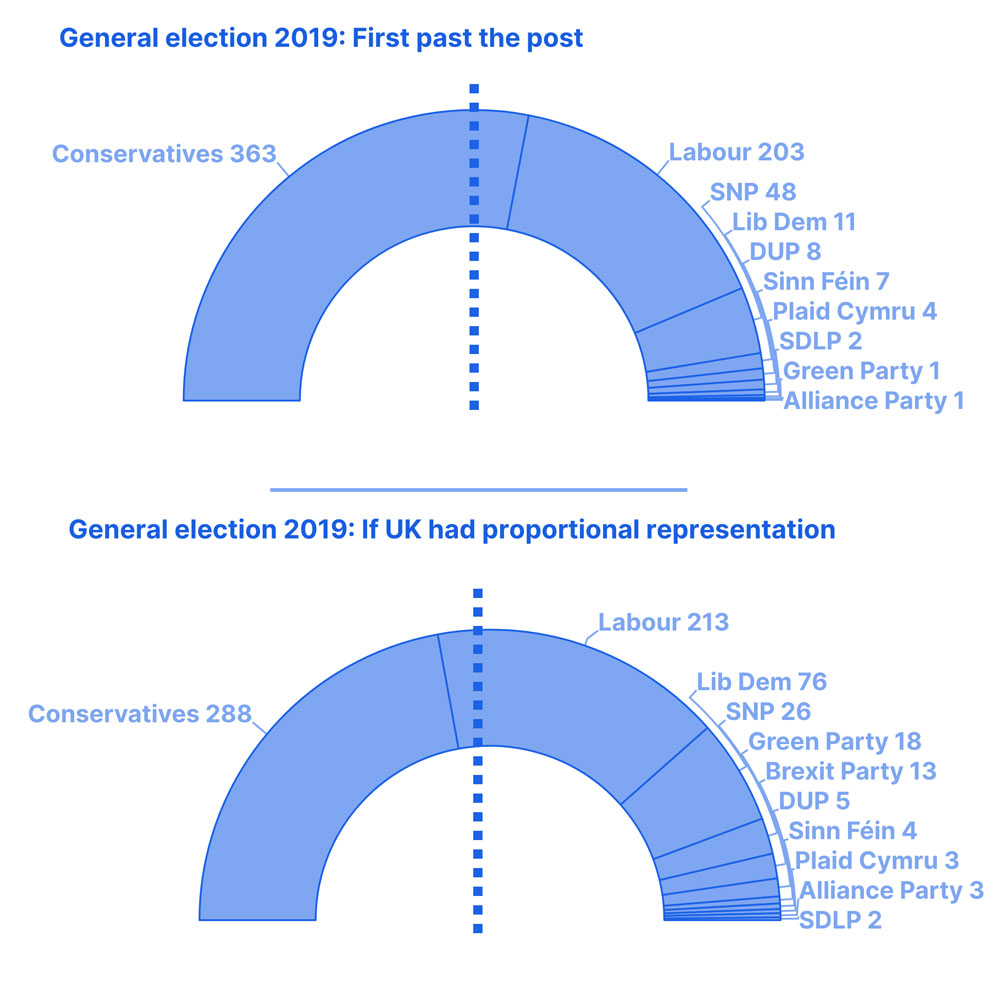

In our current electoral system, first-past-the-post, the Tories are wildly overrepresented – they have a large parliamentary majority on a 44% minority of the overall vote. That is why many pro-EU campaigners have realised that campaigning for more democracy in Britain is likely to be a necessary intermediate step to rejoin – one that can offer an immediate shared aim for progressive alliances to cohere around.

While Britain is full of democratic deficits – from the lack of a proper constitution to limitations on the franchise – the demand that unlocks the most is proportional representation. That is, instead of our archaic and absurd electoral system where voters need to constantly worry about ‘splitting the vote’ and letting in a candidate they dislike, translating percentage voters proportionally into a parliament that represents what people actually voted for.

Britain with proportional representation would be rejoining the EU sooner rather than later. That is why rejoin campaigners should support it.

The Tory assault on democracy

Making all of this more urgent are the Tories’ attempts at eroding our democracy, making it harder to hold them to account and harder to vote them out of office.

Their ‘Voter ID’ proposals, ostensibly aimed at combating voter fraud even though in-person voter fraud is incredibly low in Britain, are in reality a plan to disenfranchise millions of people who are less likely to have a valid photo ID and less likely to vote Conservative, learning from the US Republicans’ tactics of ‘voter suppression’.

Every week seems to bring a new allegation of corruption, whether it is pandemic contracts for cronies, lobbyists texting ministers or the prime minister’s infamous donations for wallpaper. In April 2021 the Electoral Commission announced an investigation into who paid for Boris Johnson’s flat makeover – then two months later the government announced, by a strange ‘coincidence’, that it is planning to take away the Commission’s powers to prosecute.

Since Brexit won the referendum, and especially since Vote Leave’s main figures took over the government, political lying has become part of everyday life. Green MP Caroline Lucas, backing a letter from six opposition parties in parliament, said: “There is a normalisation of lying to the house which is deeply dangerous, especially coming from an increasingly authoritarian government which is looking at every means to avoid accountability.”

Build the rejoin wings

A big fly in the ointment for rejoin campaigners pursuing a progressive alliance is that the main political parties’ positions on Brexit are all terrible. Labour says as little about Brexit as it can possibly get away with, out of fear of alienating Brexit-voting ‘red wall’ voters, and does not currently even have a commitment to obvious steps such as single market membership (it did previously call for “single market access” but this is not the same).

Lib Dem leader Ed Davey has been rowing back quickly from the party’s previous pro-EU commitments, apparently believing that being too identified with these positions cost the party seats in the general election. During the party leadership contest he said the Lib Dems “got distracted by the Brexit battle”: “We’ve had three very poor election results, very disappointing, in five years. I’ve got to rebuild the Liberal Democrats. And I’m not going to be diverted and distracted like we were on Brexit.”

In January 2021 Davey told Andrew Marr that the Lib Dems are “very pro-European” but “not a rejoin party”. This came after the party voted for a fudged ‘rejoin in the long term’ motion at its conference, which Davey took as licence to reject rejoining altogether.

Yet the parties’ grassroots are in a completely different position from the party leaderships. In the Labour Party – even though they are sometimes seen as the most ‘Brexity’ of the progressive parties – a huge 61% of members believe that Labour’s policy should be to campaign to rejoin the EU (YouGov, 15 April 2021). There are pro-rejoin groups organising within the party, notably Labour Movement for Europe, who signed the open letter for rejoin. But given it is such a majority in the party, it is still a heavily underrepresented position – some focused rejoin campaigning inside Labour over the next few years could pay off in a big way later.

The Liberal Democrats, meanwhile, recruited much of their current membership out of the Remain movement, using it to rebuild the party after the 2010 coalition – even though some have since quit, rejoin support is still likely to be even higher than Labour’s figure, which is why the leadership faces a battle in motions debates. Lib Dem rejoiners need to keep up the pressure so that the leadership cannot get away with fudging the issue next time.

Over the next few years, the more we can do to shift the position in every political party, the better the hopes firstly for persuading people to back a progressive alliance, and then for getting good policy positions on the EU if a progressive government is elected.