Chapter 7: Disunited Kingdom

So far we have assumed that the UK will hold together. One elephant in the room we need to look at, however, is the UK’s multifaceted constitutional crisis. The UK, despite the Tories’ occasional claims, is not ‘one nation’ – it is four. (Or three and a bit, since Northern Ireland is not exactly a nation, which is part of the problem.) EU membership was one of the key factors holding together this unusual, cobbled-together country – without it, the fractures between the UK’s nations, which were already growing, are rapidly reaching the point of no return.

Nothing in this chapter is intended to imply a value judgment about whether the break-up of Britain would be ‘good’ or ‘bad’. In reality it would have both advantages and disadvantages. Our claim instead is that, whatever you think of it, this is the road Britain is currently on unless it rejoins the EU. In other words, it can rejoin the EU as one UK, or it can disintegrate and then see individual nations rejoin the EU one by one.

Scotland wants to rejoin

Scotland voted Remain in the EU referendum by 62% to 38%. Not a single council area in Scotland had a majority for Leave. It could not be clearer that Scotland rejected Brexit.Unlike English political parties, the SNP is enthusiastic about rejoining the EU, calling for an “independent, European Scotland”. This is only strengthened by the fact that despite overwhelmingly rejecting Brexit, and then having no say in the Brexit deal, Scotland has been heavily affected by the mess – for example, much of the fishing industry that has collapsed is Scottish-based.

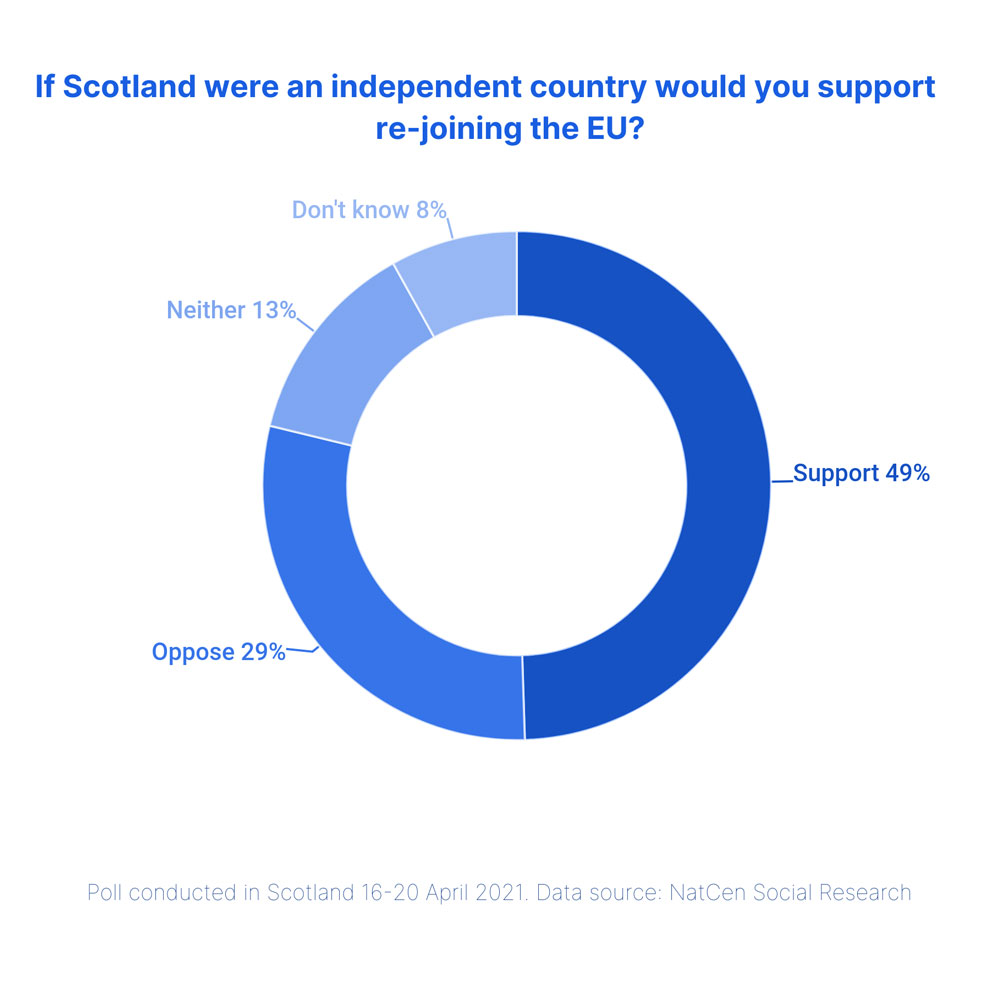

In polling 49% of Scots back rejoining the EU after Scottish independence, compared to just 29% who oppose it.

Former European Council president Donald Tusk signalled in 2020 that any application from Scotland for EU membership would be welcomed. Cultural figures from across Europe have also called on European leaders to “ensure that the EU clearly signals a path for Scotland to become a member” ahead of any independence referendum.

The Scottish people want to rejoin the EU. The only question is whether it does so as part of the UK, or as an independent country. In effect, any future Scottish independence referendum will no longer be a question of ‘part of the UK or go it alone?’ – it will be a choice of unions: ‘part of the UK or part of the EU?’ Rejoining the EU could even prove to be the decisive factor in Scottish independence, adding enough extra percentage points to the Yes vote to get it over the winning line.

A united Ireland

Another way Britain could break up – and the deepest fear of the Northern Ireland unionists – is through Irish reunification. The Good Friday Agreement includes a provision for a referendum known as a ‘border poll’ if enough of the population want it. The clause says that the secretary of state for Northern Ireland must call a border poll “if at any time it appears likely to him that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland”. While this is a somewhat unclear test, it could include opinion polling or electoral majorities.

There is not currently a majority in Northern Ireland for Irish reunification, whichever measure you use, but there is 51% support for holding a referendum in the next five years (LucidTalk, 24 January 2021). Unionism is in deepening crisis. The DUP – which at one point could have insisted on the ‘UK-wide backstop’ plan (ie. whole-UK Single Market membership) as a condition of propping up the Tory government – has ended up with a poor balance sheet for its two years of confidence-and-supply support. It got a trademark Boris Johnson betrayal, some ‘bung’ funding for Northern Ireland infrastructure, and the existence of the union it wants to defend placed in peril. As often with parties in crisis, the DUP has been unable to choose and keep a leader after collapsing into infighting.

Economically, the huge problems created by the Brexit deal are causing Northern Irish trade to rapidly shift away from the UK and towards the Republic of Ireland. According to Ireland’s Central Statistics Office, the value of exports from Northern Ireland to the Republic almost doubled in February 2021 compared to February 2020, from £126 million to £246 million. The Republic’s exports to NI were also up by almost 40%, from £146m to £201m. Trading with the UK has become a nightmare – but trading with Ireland is as easy as it ever was. It is no surprise that Northern Irish shops choose buying from the Republic over empty shelves.

The Tories surely know that the Brexit deal placed Northern Ireland much closer to the Republic of Ireland and so to the EU than to the UK in economic terms, and if nothing changes, eventually the politics and constitutional arrangements look likely to follow.

Little England

If all of this came to pass, the remainder of the UK would be England and Wales, and with the beginnings of support for Welsh independence, maybe England alone in the end. Would this ‘rump’ country really expect to keep its already diminishing geopolitical power, really expect to be able to pursue an ‘independent trade policy’ while occupying half an island off the coast of Europe, really build the hard border with Scotland that would be necessary to enforce that?

The nightmare scenario after the break-up of Britain is that those of us who live in England will be stuck in a right wing country, stuck with huge Tory majorities, stuck with no chance of rejoining the EU. But in this scenario – and remember the collapse of the UK would take a long time to play out and bring with it many controversies – it seems strange to assume that such a minor nation would be able to continue with the Brexit project as planned. This Little England would not want to join the EU, but ultimately it may lack the clout to do anything else.

Brexit is a story about Britain in decline, and part of its population’s nostalgia for a lost past that never really existed. In the end, Brexit may yet be the end of Britain.